Spirituality and Materiality

on Serbian Frescoes

OLIVER TOMI]

Fresco Gallery in Belgrade is one of the first galleries in the world to show copies of medieval works of art. There were a number of reasons for its opening but two are the most prominent. First, considering that in 1459 the Serb State succumbed under the long centuries of Turkish occupation, a larger part of movable treasure was either destroyed or robbed. Only frescoes were somewhat preserved, decorating the walls of monasteries mostly tombstones of Serb rulers and feudal lordsí foundations. To be peaceful eternal resting-places of the buried and silent homes for monks, monasteries were built away from the main roads and towns. So, they were shelters from Turks who would not gladly go deeper into forests or roadless areas as long as the tribute was regularly paid. However, today this is not good for tourists and others concerned who would have to go a long way if they want to see all monuments of Serb medieval heritage. Exhibiting the copies of Serb frescoes in the Gallery makes possible to see at least, even during a short visit to the capital, the most beautiful frescoes produced thanks to old Serb benefactors.

Another justification for the Galleryís existence is a documentary value of the copies themselves. They perfectly exactly reproduce the state of a fresco at the very moment of its emergence, each scratch on it, and even the minutest one. A fresco may be accidentally damaged or even destroyed in the meantime (as it happened during the latest events in former Yugoslavia), so a copy remains an important document to be used for its restoration.

It is impossible to provide a brief history of Serb wall painting herein for the lack of space, therefore only some basic facts will be presented. Medieval Serbia, being an Orthodox Christian country, belonged to Byzantine cultural and artistic world. So, models for constructing and wall painting of Serb churches, and even painters at the beginning, came from Greek areas, particularly from Constantinople and Thessalonica, the largest artistic centres of the eastern Christian world. That is why Serb medieval art is more dedicated to painting than to sculpture (prevailing in the West), using fresco and icon painting techniques, while stained-glass windows were completely neglected. Very little daylight penetrated into Byzantine and Serb churches but this was done on purpose because the stress was on mystical impression that candles produced by illuminating sky-blue and golden background in wall paintings and icons. All Serb artistic principles were taken over from Byzantium as early as during the Nemanya Dynasty (1166-1459).

A famous "White Angel" from the Mileseve Monastery fresco (1222-1224) is only one part of the scene from Chrism-bearer on Christís tomb. Actually, such scene (like the Descent to Hades) was used in Orthodox art to represent Christís Resurrection. Unlike Catholic art, where the very moment of Christís coming out of the grave is presented, the Orthodox world strictly adhered to the Gospel text. It said that the already empty grave and an angel on it was found by women who had come to anoint Christís body with precious oil i.e. chrism. This scene is found above the composition of the founder, King Vladislav (who abdicated in 1242), where he is giving a model of the church to Christ, through Mother of God, to keep it, and below is Kingís tomb. A message is clear: by expressing his belief in Christís resurrection, the founder himself hoped to resurrect on the Last Judgement Day, and so he presented Christ with the church, recommending himself to his mercy when the destiny of the living and the dead was judged.

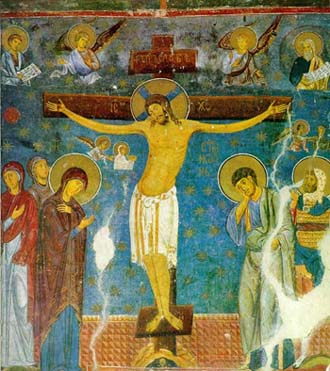

A

symbolic value of Orthodox medieval painting can be clearly seen in the

Crucifixion in the Studenica Monastery, in the Mother of God Church the

first to have inscriptions in Old Church Slavic language thanks to archbishop

St. Sava (+1236). A painter did not tend to realism but individual elements

turned into symbols: a hill where the cross is designates the Golgotha

hill with Adamís skull at its foot Ė blood is dripping from Christís feet

onto the skull, which means redemption for the Primordial Sinn by means

of sacrifice. A low wall in the background designates Jerusalem and, apart

from the actors of happening, there are personifications of the Synagogue

(a small female bust which the angel moves away from Christ under His left

hand) and the Church (a female bust too, which the angel brings up to collect

the blood dripping from the wound on Christís right flank). This, however,

does not mean the rejection of the Old Testament but its accord with the

New one, because the prophets Moses and Isaiah announcing the Crucifixion

and death of Godís son are depicted in the uppermost part of the composition.

The inscription "Emperor of Glory" means that Christ conquered Death by

his own death and the up to then disgraceful symbol of cross he elevated

to the symbol of Glory and victory.

A

symbolic value of Orthodox medieval painting can be clearly seen in the

Crucifixion in the Studenica Monastery, in the Mother of God Church the

first to have inscriptions in Old Church Slavic language thanks to archbishop

St. Sava (+1236). A painter did not tend to realism but individual elements

turned into symbols: a hill where the cross is designates the Golgotha

hill with Adamís skull at its foot Ė blood is dripping from Christís feet

onto the skull, which means redemption for the Primordial Sinn by means

of sacrifice. A low wall in the background designates Jerusalem and, apart

from the actors of happening, there are personifications of the Synagogue

(a small female bust which the angel moves away from Christ under His left

hand) and the Church (a female bust too, which the angel brings up to collect

the blood dripping from the wound on Christís right flank). This, however,

does not mean the rejection of the Old Testament but its accord with the

New one, because the prophets Moses and Isaiah announcing the Crucifixion

and death of Godís son are depicted in the uppermost part of the composition.

The inscription "Emperor of Glory" means that Christ conquered Death by

his own death and the up to then disgraceful symbol of cross he elevated

to the symbol of Glory and victory.

In the Sopocani Monastery (1263-1276) there are probably the most beautiful 13th-century frescoes in Europe. The painters coming from Constantinople depicted them for Serb King Uros I (1242-1276). The largest among the frescoes is the scene of The Ascension of the Virgin Mary painted in its common place, on west wall. Christ is accepting his Motherís soul, surrounded by the assembled apostles grieving and angels flocking together. Extremely impressive is the outstanding beauty of figures that can be compared with the greatest creations of ancient art for their proportions, draperies painting, postures, features and expressions of their faces. Ancient pagan art inspired Byzantine artists, as well as Orthodox ones, again and again once in a few centuries. In the second half of 13th century that return to classical beauty and style was so strong that it was called the Palaeologus "Renaissance" (after the name of the last Byzantine ruling dynasty).

The Palaeologan style was at its "classical" stage when Serbia was ruled by King Milutin (1282-1321), the greatest among all founders from the Nemanyid Dynasty. In the Studenica Monastery he built the so-called Kingís Church, where walls were covered with frescoes immediately after 1314. King Milutin even established a royal painting workshop that was in charge of two famous painters from Thessalonica, Michael Astrapa and Eutihios (whose activity can be followed from 1294-1321). Compared to the style in Sopocani, there were very many changes: scenes became small to increase their number in churches, and within each scene the number of figures and details was increased, their size being reduced. Each scene was to tell a story, therefore the style was called "narrative". Painters still adhered to ancient principles and even made them more profound. Namely, figures were more plastic than ever before and sometimes were presented in several planes to make space deeper. However, this can not be understood as an attempt of illusionism practiced by Giotto in Italy. Here, the space with architectural background is reduced on purpose and used only as a framework for a story and dramatic elements, and perspective applied is so-called "inverse" i.e. nearer objects are smaller and those farther away are bigger. Thus, viewerís attention is directed to the foreground but not to infinite distances.

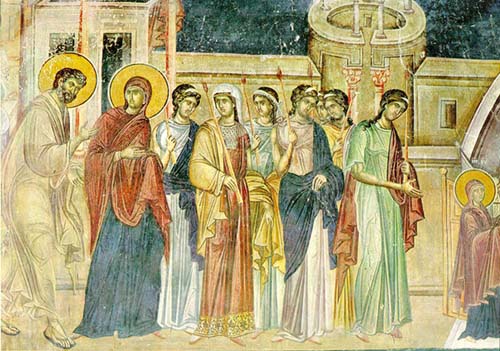

After

the extinction of the Nemanjid Dynasty (1371) and the Battle of Kosovo

(1389), the borders of Serbia shrank northward due to Turkish invasion,

and the best artists and intellectuals of the time were coming to Serbia

from the entire Balkans. The artistic style of that time was termed Moravski

after the name of the Morava river basin. Bogdan, one of the most powerful

feudal lords of the then ruling Serb Despot Stephen Lazarevic, built the

Kalenic Monastery, while the frescoes were painted before 1413. Some people

found likeness with artistic work of Andrey Rublov in Russia. Others were

more inclined to recognize master Radoslav, also standing out for his illumination

of manuscripts. The work of this universal artist reflects the spirit of

a new time which although did not lead Serbia to the renaissance as known

to the West but surely to further development of medieval (Byzantine) art,

if only it were not for Turkish conquest. In religious scenes, such as

the Wedding in Cana, elements and details from everyday life occur. It

may be even stated that if it were not for Christ and Mother of Godís presence

in the scene, it could be nearly a genre scene of a moving wedding ceremony

at the Serb Despot court. The atmosphere it creates is lyric melancholy

and tranquility, quite contrary to uncertain daily life and war raging

on the Balkans.

After

the extinction of the Nemanjid Dynasty (1371) and the Battle of Kosovo

(1389), the borders of Serbia shrank northward due to Turkish invasion,

and the best artists and intellectuals of the time were coming to Serbia

from the entire Balkans. The artistic style of that time was termed Moravski

after the name of the Morava river basin. Bogdan, one of the most powerful

feudal lords of the then ruling Serb Despot Stephen Lazarevic, built the

Kalenic Monastery, while the frescoes were painted before 1413. Some people

found likeness with artistic work of Andrey Rublov in Russia. Others were

more inclined to recognize master Radoslav, also standing out for his illumination

of manuscripts. The work of this universal artist reflects the spirit of

a new time which although did not lead Serbia to the renaissance as known

to the West but surely to further development of medieval (Byzantine) art,

if only it were not for Turkish conquest. In religious scenes, such as

the Wedding in Cana, elements and details from everyday life occur. It

may be even stated that if it were not for Christ and Mother of Godís presence

in the scene, it could be nearly a genre scene of a moving wedding ceremony

at the Serb Despot court. The atmosphere it creates is lyric melancholy

and tranquility, quite contrary to uncertain daily life and war raging

on the Balkans.

The

Manasija Monastery (1407-1418) is the foundation of Despot Stephen Lazarevic

(1402-1427), where he himself was buried. In the Holy Trinity Church the

frescoes were painted by the best artists of those times, most probably

coming from Thessalonica. The frescoes are outstanding for their magnificent

harmony of precious sky-blue azzurro and golden foil surfaces that have

always been abundantly used in Orthodox art. Among the most beautiful ones

are portraits of holy warriors in choirs, as if they posed prior to the

beginning of some tournament. These are no longer ancient armored soldiers

with old-fashioned arms handed down from generation to generation in painter

manuals, but nearly modern knights from Despotís suite Ė from arms to most

fashionable patterns of valuable textiles. After all, it is known from

written records that the Despot himself chose clothes for his courtiers

and forbid bad manners and talking loudly. Such controlled behavior and

sophistication feature those warriors without diminishing their vigor and

believersí faith that holy warriorsí arms will protect them from godless

Turks.

The

Manasija Monastery (1407-1418) is the foundation of Despot Stephen Lazarevic

(1402-1427), where he himself was buried. In the Holy Trinity Church the

frescoes were painted by the best artists of those times, most probably

coming from Thessalonica. The frescoes are outstanding for their magnificent

harmony of precious sky-blue azzurro and golden foil surfaces that have

always been abundantly used in Orthodox art. Among the most beautiful ones

are portraits of holy warriors in choirs, as if they posed prior to the

beginning of some tournament. These are no longer ancient armored soldiers

with old-fashioned arms handed down from generation to generation in painter

manuals, but nearly modern knights from Despotís suite Ė from arms to most

fashionable patterns of valuable textiles. After all, it is known from

written records that the Despot himself chose clothes for his courtiers

and forbid bad manners and talking loudly. Such controlled behavior and

sophistication feature those warriors without diminishing their vigor and

believersí faith that holy warriorsí arms will protect them from godless

Turks.

Oliver Tomi}

The author (1963) holds MA degree in the History of Art, is a curator of the National Museum, Belgrade and assistant lecturer in "General History of Medieval Art" at the Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade, History of Art Department. He has published a number of professional and scientific papers.